Rabbi Shoshanah in israel

Listen, Learn, Witness

|

Sermon for May 24, 2024 - Shabbat Behar Rabbi Shoshanah Tornberg I just returned a few weeks ago from a powerful and meaningful trip to Israel and Palestine. Travel often involves seeing the sights. As tourists--even mission-oriented tourists--we look at a foreign place we visit as a chance to take in the meaning of a place. And, so, we start with the obvious:

But, I have always felt a strange otherness to my touring. It often feels like pretending at living. How do you really get a sense of the meaning of a place and the lives of the people living there? How do you find this meaning without turning the lives of other people and peoples into a reflective story about yourself? In other words, how do we prevent ourselves from failing to truly see another? The people who live in the places one tours likely do not spend their days at tourist destinations. They instead draw meaning from the

Without immediate family in the land of Israel it is hard for me to enter into this place. But, for the first time since I traveled anywhere that was not home, I felt, on this trip, closer to the meaning of the land and its people. Israel is about so many things. But, most of all, it is a land that is not just a story about itself. It is a land that is about its people. The people who lived there. And the people who live there. Now. Now is hard. I could have travelled to see the sights and talk with a few volunteers. I could have worked on a kibbutz in need of more labor or assisted getting meals to soldiers. And these ways of encounter would have been true. And they would have had merit. But, the planners of my trip did something remarkable: They gave us the chance to see the people of the land. All of its people. Of course, we learned from Israelis first-hand about the terror and psychological toll the Oct. 7 attack and the subsequent war is taking on Israeli minds and hearts. But there was more: It was a remarkable moment in my Jewish education, because we began to talk about and with Palestinians. We did not shy from drawing attention to the experiences on the other side of the borders. This is real. And this is part of the story of Eretz Yisrael. And if we are to tell a whole, honest, morally forthright story, we have to tell of this, too. If Israel is to find wholeness and a functioning democracy, it must stop being an occupying force. This role is eating at the core of what it means to be a Jew today. Just ask Yehudah Shaul, the founder of Breaking the Silence and the over 1000 soldiers who have joined him in speaking out against the immorality of the occupation from the perspective of their IDF service in the West Bank. There are many voices in Israel rising against the tide of an old way of seeing things. And they are up against mighty foes. I was horrified upon my return to the United States to learn of the far right-wing settlers who enacted operations to intercept the life-saving food that humanitarian aid groups were trying to deliver to residents of Gaza. With humanitarian aid being limited from entering the Strip, Palestinians starving was and is becoming more severe. Far-right Israeli settlers began attacking aid convoys destined for Gaza, while Israeli police officers stood on the side watching the extreme settler violence unfold. These were the same kinds of trucks I saw outside our bus when we were in the Gaza envelope–the area of Israeli towns and communities close to the Gaza border. The food was waiting. I was also proud to see Jews begin to stand up against this corrupt and destructive sense of patriotism. “Standing Together” is an organization that works for peace and independence for Israelis and Palestinians, full equality for all citizens, and true social, economic, and environmental justice. On May 15 they launched the Humanitarian Guard: They called on citizens of Israel, both Jews and Palestinians, to stop this act of terrorism from happening, to defend humanity, and to bring an end to this extreme government. Their plans were to escort the aid convoys and ensure they reach their destination and to raise awareness about this catastrophe happening before our eyes. This week in the Torah, we learn of the parameters that our ancient law code put in place to maintain social and economic justice. The text of Behar tells us the laws about Shmita and Yovel–the Sabbatical and Jubilee years. The practice of the Sabbatical year teaches us to let the land we are farming lie fallow every seven years. This helps the land rejuvenate, and it reminds us that we do not own the land, but are merely borrowing its use from God. Once seven sets of seven years pass, we celebrate the Jubilee (Yovel)–at least we did in ancient times. This is the part of the Torah where we get the phrase, “You shall proclaim release throughout the land for all its inhabitants.”--That is, “proclaim liberty…” This phrase’s origin in the Torah refers to the release of slaves who were forced to sell their labor into servitude. It refers to the forgiveness of debts, and the reversion of land back to its original owners.t It is a way that the Torah tries to codify a huge, social and economic do-over. On the heels of my trip, it is hard to think about this vision of a do-over as we face such sorrow, suffering, and horror, in, of all places, this land. Who owns the land? Who owned the land? Who should own the land? Who has suffered? Who has been a perpetrator of hatred and violence? Who has faced injustice? These are no longer the questions that plague me. What plagues me is the question of who we are becoming. It makes me ask, who do we want to be? One of the inspiring leaders with whom I met, Maoz Inon, shared the words of Elana Kaminka, an Israeli mother who lost her son on Oct. 7. She shares her wisdom from this harrowing time, “The more quickly and effectively we learn to live together, the greater the chance for our children to see a better future in this country.” We want to be a people who value our past; we may even venerate it. Jews care about memory. But this moment calls us to do more: we must also envision and build for a future. We must find a way for us all to begin again.

0 Comments

Though our trip was short, we were lucky enough to have the opportunity to meet with some thinkers and leaders in Palestine. These folks were, at some personal risk, meeting with us in order to help us understand some of the "on-the-ground" public opinion and efforts toward ending the conflict from the Palestinian side. It was very informative. A Word About A Word: PalestinePalestine.

This word is hard for some of us to hear. We have always learned that there is no such thing as Palestine. We have learned that it is a made-up ethnic entity. We have learned that it represents a gaslighting of the Zionist project and of Jews who see our heritage as a specific people with a specific tie to the land. We learned that the Arabs made it up in 1948 to avoid having to absorb displaced Arab residents of the new State of Israel. This story may be true. But, it is also not fully true. We are in a mess, and the partner we need has an identity and a story. When we approach another to make peace, or even to make conversation or to collaborate on something meaningful, we must meet the person in front of us. We gain nothing by approaching the person we wish they were or think they should be. We gain nothing by denying their story. We can choose to do so, but not if we want to partner with them. I have used the word "Palestine" on the bimah in a non-disparaging way. A few KI members have shared their discomfort with this choice. We are not used to it. I remember the book in my school library in 1990 about this population and their struggle, and the book called them Palestinians. It used the word, "Palestine." And I was vaguely uncomfortable. Wasn't I supposed to negate this? Here it was in my school library. I have felt this discomfort, even back then. Here we are today: I sat in the Millenium Hotel in Ramallah (the de facto capitol of the West Bank). There I met with Palestinian thought leaders. But, what struck me as profoundly as their words were the words on the tissue box and hotel-branded pens in front of me: "Millenium Hotel, Ramallah, Palestine." This sense of place and identity is real for our potential partners. It is, for them, a fact. If we want a way forward--if we want a way toward peace (if not friendship) --we must make peace and make friends with this word. Using the word Palestine--without denigration or negation--is essential to the future of this conversation, if we dare to converse.

doorless bomb shelter at the site of the Nova Festival Massacre doorless bomb shelter at the site of the Nova Festival Massacre A Note About Bomb Shelters It has been a long time since I have lived in Israel (twenty-four years). I was there just before the second intifada. At that time, it was not the case that every home and building had a bomb shelter, as is the case now. So, I was amazed to learn how and for what kinds of protection the shelters are constructed. I pictured a "duck-and-cover" era bunker in the ground, filled with food, supplies, and sleeping cots. Most bomb shelters in Israel are very different than this description. Bomb shelters are meant to protect people from bombs descending from above. Additionally, should there be damage to the shelters, it is important that those seeking shelter would be able to exit the rubble. As such, bomb shelters do not have doors that lock. A lock would prevent exiting. In fact, some of the shelters I saw during my travels did not even have doors. They are constructed like a square, concrete tube, with walls on either end. These walls are constructed about a foot or more from the edge of the tube, leaving a gap for people to enter and exit. Again, this is a reasonable design for quick entry, easy exit, and protection from bombs from above. Another design has no door at all: It is a concrete structure with no door that looks like a small bathroom in a national park--you enter and then turn a corner 180 degrees, so that you are ensconced in the concrete walls--much like entering the bottom of a capital letter "G". Again, these designs are made for aerial bombs. They are not designed to protect from terrorists. The logic here is that if terrorists were to come, they would be intercepted by the IDF before they could get to the populace in any great numbers. In Her Own Words Here is a video of Hila talking about that horrifying morning, when twenty people in her village were murdered:

Neighbors and Enemies There was a resident who shouted to the terrorists: I am not your enemy! Indeed, these residents were among the many Israelis who prayed, hoped, believed in, and worked for peace and justice between them and their Palestinian neighbors. It is a deep, sad irony that these were among the first victims on Oct. 7.  mandalas made by Netiv Ha-Asara residents under direction of Bilhah Inon. These works of art made from recycled materials decorate one of the buildings in Netiv Ha-Asara mandalas made by Netiv Ha-Asara residents under direction of Bilhah Inon. These works of art made from recycled materials decorate one of the buildings in Netiv Ha-Asara Bilhah and Yaacov Inon: Peace, Love and Works of Art (The Things We Lose) My May 10 blogpost entitled, "Prophecy and Protest" tells the story of Maoz Inon. Maoz is the tourism professional and peace activist who builds neighborhood economies and forges business partnerships with Palestinians in Israel. He also mourns his parents, Bilhah and Yaacov who were killed on Oct. 7. Bilhah and Yaacov Inon, Maoz's parents, were killed on Oct. 7 when their home in Netiv Ha-Asara was burned down to its foundation by terrorists. Yaacov was an agronomist who envisioned and worked with a team to develop a more productive strain of sesame that could be grown in Israel. Bilhah was an artist, who utilized recycled materials in artwork long before it was a "thing." Before she died, she was working with community members on projects, teaching them to make mandalas. Outside their decimated home one finds a beautiful "junk"yard full of old equipment interesting pieces of found and created art--all part of Bilhah's workshop. All that remains of the house is its floor, laid out like a large-scale model of a floor plan, as if on paper. Paper that did not burn. The site is another of too many memorials.

In the days before I left for Israel, I began, in my sketchbook, to try my hand at drawing anemones. These red flowers are the national flower of Israel, but also represent the land and its people. The Hebrew word for this kind of flower is kalanit (kalaniot is plural). It represents hope, resilience, and beauty. I was struck by the many works of art I have seen online since Oct. 7 featuring peaceful kibbutz fields of red flowers. (Artists illustrate reactions to Oct. 7 at Jerusalem's Outline Festival | The Times of Israel).  Teaching myself to draw them was a way to begin turning my heart to the journey ahead. Kalaniot graced the park I used to pass when I lived in Jerusalem, and they stood out as part of the unique flora of the land. In my days of travel on this trip, there were particular kalaniot that stood out. Unlike the blossoms that fluttered outside kibbutzim and in the parks of Jerusalem, these kalaniot were permanent. They were made to blossom throughout the seasons, a symbol of eternality in the face of incalculable endings. They were part of the memorials that had been set up at the site of the Nova Music Festival.

The site was crowded with many paying tribute, offering witness, and grieving. Some who were there at the same time as our group were clearly grieving close loved ones whose memorials stood before them. There were prayer groups, and visiting school and community groups. There were families and lone individuals. There were Jews and some non-Jews of all walks of life mourning and paying homage. Peppered throughout the site were art installations and memorials. Across the road was a nascent forest with a tree planted for each life that was taken that horrible day.

I spoke to a member of our group about her experience with this tragedy. She said she did in fact know one of the hostages--Hersh Polin-Goldberg--who was taken from the Festival. We believe he is still alive. The sorrow in this place is all too real. Some of the faces on the memorials looked so much like my daughter. She is twenty-one, and had we been living in Israel would likely have found her way to this festival. Being in the rarefied space, made sacred through unwilling sacrifice, I felt the heartbreak and the chill, despite the heat. I also saw the yearning, ever-more- urgent hope for those who were taken captive; for those we prayed were yet still alive. We lacked words enough to meet the gravity of this place. All we could do was be present. We could witness. I got separated from my group, lost in the wash of sorrow, weaving my way through the grounds. When I reunited with them, they were standing in a circle under some trees. One of our group, Cantor Jack Chomsky, was chanting El Maleh Rachamim (the prayer for the dead) with a depth and rich sadness I had never heard. We Jews are blessed to have prayers to utter when we cannot find words of our own. On the third day of our trip, two stories inspired me in particular. They are the stories of Yehudah Shaul and Ibrahim (not his real name).

Yehudah Shaul Among the journeys that we took that day were a trip to the West Bank. Guiding our group throughout the day was Yehudah Shaul. Yehudah’s story is a moving example of how a person can grow and change as we age and learn. It is also an example of courage and leadership. Yehudah was brought up in Jerusalem in an Orthodox family. As a teen, he studied in a yeshiva based in the West Bank. In 2001, he began his military service. Shaul served as an infantry combat soldier, and eventually he served as a commander during the second intifada. Two of these years he served in the West Bank. Shaul was following a path that was dutiful, patriotic, and imbued with religious obligation. It is the Israeli path for most. But, during his IDF service, there were things—orders, deeds, and operations—that gave him pause. Some of the things he was required to do seemed, well, less than moral. They ran counter to his understanding of Jewish values. As a soldier, he found no place and no voice for these concerns. A soldier, according to Shaul, might have questions, but you have a team counting on you to perform your part of the operation. Your buddy is going off guard duty at 6:00, and you need to replace him. Life and events in the IDF flowed along, stopping neither for a breath, nor for an ethics discussion. When Yehudah finished his army service, his concerns did not abate. He wanted to give voice to what felt was wrong about the deeds he had conducted in the military. He got in touch with old commanders and some fellow soldiers, and in speaking with them he learned that he was not the only one who felt uncomfortable—and in fact they, too, believed that much of what they were doing was wrong. Soon after completing his army service, Shaul founded Breaking the Silence.[1] Breaking the Silence is an organization of Israeli ex-military who engage in activism in support of Palestinians who are unjustly victimized by the Israeli Government and the IDF. Today, Breaking the Silence involves over 1000 soldiers and ex-soldiers fighting against the Occupation. Shaul could see that the IDF had long ago transformed from an army of defense to an army of occupation. He wanted to be part of an army of defense. Having stepped away from directorship of BTS in 2019, Shaul continues to support the organization as a board member. Since leaving BTS, together with Dana Golan, Shaul founded Ofek: The Israeli Center for Public Affairs[2], an independent think tank. Their mission is to help advance a peaceful resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Here is how he puts it: We believe that only by ending the Israeli military occupation can the right to self-determination of Israelis and Palestinians alike be realized. Our vision is of two democratic states living side-by-side in peace. To achieve this end, Ofek performs rigorous research, presents policy solutions, and engages in advocacy in Israel and around the world. Yehudah was the guide who led us through Khirbat Zenuta and shared with us the background of how the village came to be blocked off by settlers and ultimately decimated by them (see blogpost for May 10). Ibrahim With Yehudah as our guide, we also had the honor of meeting Ibrahim. He quietly and humbly welcomed us to the patio outside his house. Yehudah and Ibrahim clearly had worked together and built a relationship over time, and Yehudah acted as our interpreter. We had made our way to Ibrahim’s home on foot, since the giant boulder placed at the head of the road by radical settler Inon Levy (see May 10 post) made driving to the village impossible. Our group sat outside his modest home in his tiny farmyard. There, Ibrahim and his wife were raising their family and trying to make a living. Much like the residents of Khirbat Zenuta, they have struggled for decades against the encroachment on access to their livelihood and growing, daily threats to their safety. Years ago, one of Ibrahim’s relatives was killed by a Jewish settler. That settler was later killed, and the IDF arrested Ibrahim and a few other young Palestinians. He was seventeen years-old. The arresting officials made him and the others lie face down with their noses on the ground for fifteen hours. They did not allow bathroom breaks, and they did not tolerate the moving of the teens’ heads to the side to breathe. Sometimes they let him up for questioning. He had no knowledge of what had even happened. Eventually, they released Ibrahim and the others as the trail of the investigation moved in a different direction. As Ibrahim made his way back to his village, he realized that he needed to take an indirect route. He did not want to encounter attacks, intimidation, or violence from Jewish settlers in the area. He took a wide, roundabout path back to his home, only to find that, as he crested the hill, the place where his village was supposed to be had no village. Settlers had destroyed it in his absence. Ibrahim was seventeen. He and his community were surrounded by a Jewish army who subjected him to torture. He and his community were surrounded by the constant threat of Jewish settler violence and land grabs. And, now, his village was destroyed. The young Ibrahim was prepared to commit to a life of violent resistance. But, then something unexpected happened. It was something for which he had no previous framework: Jews started showing up in his community with food and supplies. Jewish peace activists and aid workers revealed a Jewishness about justice, compassion, and serving the needs of others. He had never encountered such a version of Jews or Judaism. This powerful realization catalyzed Ibrahim to turn away from a path of violence to one of peace activism and partnership with Israelis (like Yehudah) also seeking peace and justice. It was clear from his farm and home that the family did not have a lot. Life and livelihood are hard, and they are made harder by the pressures from those with more power than this family. A few ducks made noise in the yard. A chicken crossed the patio. There were old pots, gardening equipment, and various vines and small garden plots. And, yet, we felt so welcomed, especially when Ibrahim’s sixteen year-old son, Mohammed silently came around with tiny cups of sweet tea. Just before we left, Ibrahim ceded the “floor” to Mohammed. This sweet and charming teenager stood before a group of American rabbis and shyly tried his (very good) English. He told us about kids at his high school who had been killed by settlers, and how he has been trying to deal with this trauma among the many he and his family face. He looked like my own child, sitting in class across the ocean. Mohammed wants to come to university in the United States. As he spoke, I thought back to the horrible incident Ibrahim described from when he was seventeen. I thought about how Jews showed up to support and help him. I thought about how these deeds changed the trajectory of his life. I thought about how this young man in front of us may never have existed had his father chosen the obvious path of violence. [1] Breaking the Silence [2] Ofek (ofekcenter.org.il) On May 7 we met with Meital Bonchek.[1] Unlike many of the secular activists we met, Meital is an Ultraorthodox woman who finds herself politically adrift and connected to strange bedfellows. Having grown up and raising her own family in an Orthodox community in Israel, Meital unexpectedly found her way to a different kind of activism. And she has found her identity as an Orthodox feminist.

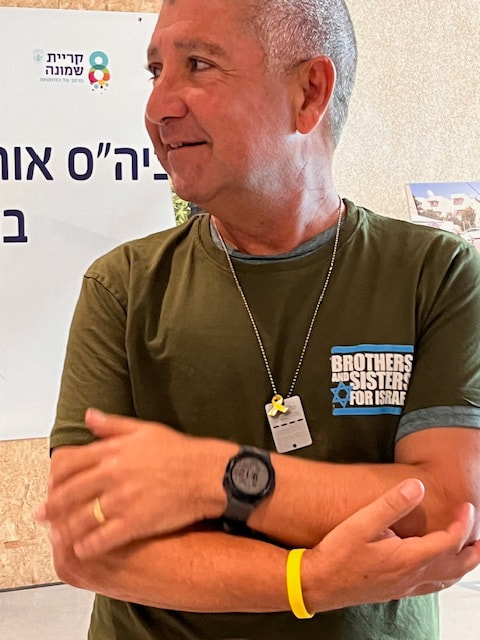

While attending Hebrew University as a young woman, Meital came across a book in the library on sex trafficking. She had never known of this phenomenon and began to explore whether it was a problem in Israel. Of course, she did learn that people are trafficked against their will for sex work, even in the Holy Land. Bonchek took a step that is unusual in Israel: she reached out to activists working on this issue on the left. As an Orthodox woman, the left and its activists were a foreign entity. And yet she forged ahead to build coalitions “across the aisle.” What is remarkable about Meital’s story is that she did not “reach across the aisle” and stay there. She built partnerships, but used what she was learning to bring this taboo issue to her own community. Though Bonchek’s subset of the Orthodox community in Israel is not accustomed to pursuing “social justice,” its members are deeply ensconced in the Jewish concept of chesed—that is, acts of kindness that serve others. Bonchek and others are driven by the teachings of the prophets that we have ethical responsibilities to one another. (Much like Reform Judaism!) Deeply driven by the stories, suffering and abuse of trafficked people, Bonchek began to explore how feminism could fit into the ethical edifice of halachic[2], Orthodox life. And, in doing so, she began to build a coalition of Orthodox, and secular, leftist activists. As part of this work, Bonchek began working with an organization called Ma’aglei Tzedek, which is a social justice group within Orthodoxy. She also serves as the Deputy Director of the ‘Briah Foundation.’[3] As the Founder and Co-Director of the Coalition of Religious Organizations to Combat Prostitution, Bonchek spoke to the Israeli Knesset about the issue. She has been instrumental, too, in shifting the conversation in the “religious” community away from the blaming and shaming of women involved in prostitution. Orthodox, traditionally right-wing voices joined together with voices from the left, creating a partnership that has mobilized a national movement: a movement promoting a law to criminalize clients of prostitution.[4] The law they helped promote with activists from the left criminalizes not those who are engaged in prostitution against their will, but rather those choosing to utilize these services. Until the law passed, only traffickers were subject to criminal penalties. And, until Bonchek and her growing team began their activism, there were many in the Orthodox rabbinate who tended to blame the trafficked victims as moral failures. It is no great surprise to anyone reading this that current Israeli politics is deeply divided. One’s identity is either one thing or the other. But, Bonchek was able to forge a coalition of left and right that led to a national movement. She shared with our group an insight, “We can belong to more than one group. Our identities are sometimes fluid.” Straddling communities as she now does, Bonchek found herself in the astounding position of attending recent government protests of the right (in support of the proposed judicial overhaul) AND of the left (against it). "Her people" were in both camps. Rather than feeling adrift and out of place in either community, she is beginning to find a home in two different places. Even so, she describes herself as having no political home. She is also in search of a new spiritual home. Coda When we asked about giving up land for peace—even the settlements where many in Bonchek's community reside—she broke the mold of the Ultraorthodox line. The right-wing idea that we should not give land for peace was not, for Bonchek, the edifice that it seems from the outside. Land for peace, she shared, would of course be worth it if it were really, actually, reliable peace. In sharing this view, Bonchek opened a surprising and unexpected crack in the occupation debate: An important part of what is standing in the way of land-for-peace negotiations on the right is not necessarily an unwillingness to bend, but rather a reticence to believe that true peace is possible. [1] Religious-Zionists join fight against Israel's sex industry - Israel News - The Jerusalem Post (jpost.com) [2] Halakhic - definition of Halakhic by The Free Dictionary [3] The Briah Foundation [4] Seeking prostitution services is now illegal in Israel | The Times of Israel  Ronen Koehler meets with our group of rabbis at the Brothers and Sisters in Arms Civilian Headquarters near Tel Aviv. Ronen Koehler meets with our group of rabbis at the Brothers and Sisters in Arms Civilian Headquarters near Tel Aviv. On May 7 we visited with Ronen Koehler of Brothers and Sisters in Arms in G'lilot.[1] Ronen shared with us the germination of his organization. Like many Israelis, Koehler served in the IDF. Koehler has dedicated forty years of service to the Navy, seventeen of which were on active duty. He is a business leader in the areas of organizational development and IT and is embedded in the "startup nation" identity of contemporary Israel. He and many others drew attention to themselves on the world stage as the reservists who refused to serve under a government that threatened a judicial overhaul. They were part of the large and vocal protest movement that was gaining ground in the months before Oct. 7. After Oct. 7, their work shifted. In response to the war, Brothers and Sisters in Arms began providing agricultural support. Many farmers were deployed in the IDF, and many foreign national farm workers left the country. Ahim LaNeshek (Brothers and Sisters in Arms’ Hebrew name) also assisted with the thousands of evacuations of Israelis from towns near Gaza and near the northern border with Lebanon. They began to dub their effort, “K’var Ba’im,” meaning, “Here We Come.” Brothers and Sisters in Arms deployed their organizational efforts to come and get people out of dangerous areas. There were no government or IDF efforts to do so. In the first ten days of their operation, they rescued 10,000 people from places like S’derot. Koehler told our group that the residents had been abandoned in the towns near Gaza. The IDF did not come. The residents sat wondering if Hamas would come, and Koehler’s organization filled the breach. Oct. 7 was a Saturday, and by Sunday, Oct. 8, Brothers and Sisters in Arms put up a civilian headquarters for donations to take south to the Gaza envelope communities and to families who were living in faraway towns as evacuees. It was in these headquarters that we met with Koehler. Ahim LaNeshek created a civilian "war room" to meet the wartime needs of the nation. The IDF was not equipped to massively support the civilian population. In fact, the army never even arrived at Kibbutz Nir Oz. When its residents were evacuated to Eilat (where they still are), the army never came there either. It became clear early on that those in need should call upon Ahim LaNeshek. Through this and other facilities, the group executed a huge logistical operation to manage donations and distribution of supplies. Volunteers also stepped up to feed soldiers, using donated restaurant facilities. The group fed 30,000 meals to soldiers in the immediate aftermath of Oct. 7. The group also became involved in pet rescue management. Prior to the war, the efforts of Ahim LaNeshek were focused on protest and getting media attention, and overnight, they changed their efforts to serve the needs of their fellow citizens. So, out of a movement of protest that mobilized to defend democracy, Ahim LaNeshek became a giant, effective civil service organization. Countless Israelis have been personally involved in their efforts. And as the group thinks about the future of Israeli society . . . as they think about charting a course for preserving democracy, they have created and mobilized a platform of organizational and civil management so effective it will likely serve as a basis for their bid to replace the current government. Israeli Culture: Where Has It Been? Where Is It Going? Koehler shared that for many years the Israeli government has been starving its public services through politicization. We are all so proud to tout Israel as a start-up nation, but, Koehler opined, the private sector forgot the importance of the public sector. As a result, the services of the government's public sector have atrophied. In the breach left by Oct. 7, many Israeli donors (of the private sector) showed up with funding for these community needs. Israel was not just looking to the Diaspora for funding, but was stepping up itself as Israelis began to pivot their sense of civic duty. According to Koehler, Israelis have begun to understand that being a citizen in a democracy has to be more than paying taxes. Citizens have to be involved if they do not want to cede the important social questions to politicians. Israel is beginning to understand that involvement sometimes means protesting. Sometimes it means volunteering. Sometimes it means philanthropy. The prevailing ethos used to be "I did my army service, now I am going to make money." But, this is changing. Ahim LaNeshek is creating a database of people who share their values and who want to be involved in a democratic process and the growing civil society. And their message and efforts are becoming a ubiquitous part of Israeli life. Beyond the Emergency About four weeks into the war, the emergencies had been covered, and the organizational leaders could see that a longer-term effort was needed. This was when volunteer Avi Noam started over 120 kindergartens. This was when Ahim LaNeshek began to create youth activities and teen support programs. Two months ago, Koehler's team realized that it was time to get ready for the future. How can Brothers and Sisters in Arms create a sustainable civilian support organization for situations that are not necessarily emergencies? They have begun to develop a more formal organization, hire staff, and clarify their areas of focus:

In a previous post, I mentioned that Maoz Inon and Nadav Tamir talked about how this moment of crisis is an opportunity. It was hard not to hear in Koehler's remarks both the enormity of the task and compelling possibility for a better Israeli future. _____________________________ Epilogue: Our Diaspora Role For many years, since my childhood, the message I heard from Israelis and Israel was at times dismissive, and at times contemptuous of Diaspora Jewry. For one thing, a prevailing assumption in Israeli culture was that truly there could be no real safety as Jews and no “real” Jewish life outside of “the Land.” We don’t live there. We don’t know what it is like. Our points of view—our “say”—had no real weight or value in Israel. Again and again, speaker after speaker, on this trip and in other recent conversations with Israeli colleagues, Israelis are saying something different: We are not asking for Diaspora support. We are asking for Diaspora partnership. One way this plays out is in the desire on the part of many peace and democracy activists that we use our voices that decidedly are not “of the Land,” to push forward a moral intervention. We do not let our loved ones drive drunk. We may not let our loved ones choose a path of destruction. Koehler and others want our voice and our influence (especially on OUR government) to help us all recenter our moral core; to build a homeland of justice and democracy. [1] They Refused to Serve. Now They’re Supporting Israel’s War Effort. - The New York Times (nytimes.com) אחים ואחיות לנשק - למען הדמוקרטיה (ahimlaneshek.org)  silken, purple party frock discarded by the wayside on the footpath up to the decimated village of Chirbat Zenuta. This road and the village site are within sight of the nearby, brand-new illegal outpost on the neighboring hill. silken, purple party frock discarded by the wayside on the footpath up to the decimated village of Chirbat Zenuta. This road and the village site are within sight of the nearby, brand-new illegal outpost on the neighboring hill. Yesterday, May 8, 2024 we visited the site of Khirbat Zenuta in the West Bank. It's heartbreaking to call it a “site,” because as recently as Oct. 28, 2023 this was a town of 250 residents, Palestinians who had lived there for generations. We had to walk up to the erstwhile village on foot, because one of the Jewish settlers, Inon Levy[1] who recently was sanctioned by the American government used his construction and demolition business equipment to literally install a giant boulder in the middle of the road, preventing its residents from driving in and out. We also had to go on foot, because as our bus drove on the road to this village in Area C[2] of the West Bank, it was met with makeshift barbed wire fencing that Jewish settlers (with no authority or accountability) had installed in the roadway. As we made our way up the path on foot, I could see a discarded trash bag with clothing spilling out. One item, a silky purple garment on the top of this pile, sparkled in the astounding sunshine. I imagine the woman who wore this garment for special occasions: I can envision how she must have dropped it as she ran and harried from her home. She is not a dead memory, but a person still out there, still trying to live as her life and livelihood are ever squeezed more tightly. Up on the hill, just beyond, we could see what is called an unauthorized and illegal settler outpost. All Israeli settlements in the West Bank are considered illegal under international law. An occupying force is not legally allowed to bring any of their population to settle in the occupied territory. Israel does not accept this limitation, but they have agreed to some limits. The Rabin government during the Clinton administration, as well as subsequent Israeli and American administrations, have made and reiterated an agreement that Israel would freeze new settlements, assenting to only expanding previously established settlements. As a result, new settlements (outposts), which often pop up overnight through the covert operations of Jewish vigilantes and thugs, are unauthorized as well as illegal under, even Israeli law. However, the Netanyahu government looks askance at these unauthorized outposts, giving them a carte blanche for unchecked violence, intimidation, and thuggery. As the Palestinian villagers left, pushed out by encroachment on their water rights, their freedom of movement, their grazing land, and their harvest access, they also had to daily contend with intimidation by settlers, the IDF (Israel Defense Forces), and settlers pretending to be IDF. Despite all this pressure, many hoped they would be able to return in a few days. We learned all this from independent Israeli activists who work to defend these villages and their residents. These activists often escort children to school for their safety and shepherds to their fields to assist in defense against settler violence. Of course, we did not learn the story of this village from its residents. They were gone. They had fled. They had been forced out. The village was in rubble…old stone buildings were in ruins. Here and there were the detritus of households. But off to the left was the abandoned school building. It had been funded by the EU in its construction and included about five classrooms in an L formation around a courtyard. We made our way around the back wall and were met with the sight of the inner part of the L: It was a gasp-inducing disaster. I had to catch my breath. This education facility, in use but a few months ago, was strewn with bulletin boards, notebooks, whiteboards, writing implements, the dish drainer from the staff break room, a laminated train on the wall, bookshelves, textbooks, wall charts with nutrition lesson material, student work hanging on walls and from ceilings, broken windows strewn on the floors, and roofs caved in under the weight of huge tires. The villagers had thought they would try to return in a few days, when the conflict with the settlers dissipated some. But, Inon Levy and his team of outpost bullies went in the day the Palestinian villagers left and decimated the village, again with Levy’s construction equipment. There is something horrible -- perhaps because I am an educator -- in seeing the destruction of classrooms, especially with all the artifacts of education strewn about. It was a sacrilege, by which I mean it is just one more example of how the dream of Zionism--pluralistic, democratic, multicultural, justice-oriented--has been hollowed out by a racist and perverted reading of Torah. These deeds and the complicity of the government to these deeds DO NOT illustrate what it means to be a Jew, to live by Jewish values, or to make real the Zionist dream. Even if this crisis of conscience did not impinge on the rights of non-Jewish humans, we would still be called at this moment to a moral crisis: These policies and behaviors do nothing to truly protect Jews, Judaism, or the State of Israel. Continuing the banality of this kind of terror, perpetrated by Jewish settlers (in OUR names, on the world stage), further mires our people in corruption and immorality. This is not self-defense. This is bullying. We should be ashamed if we are complicit. On Yom Kippur this year, it will be a communal "chatati" if we do nothing to upbraid this madness. [1] Israeli bank freezes account of settler Yinon Levi sanctioned by US | The Times of Israel [2] West Bank areas in the Oslo II Accord - Wikipedia

Now, in the wake of his parents, Bilhah and Yaakov Inon's Oct. 7 murders by Hamas, he turned his parents’ lives’ work and teachings about

toward not just his business and community investment. For Inon, their deaths marked a shift in his path forward—like so many in our fractured and harried world, Inon had already begun to look for ways to live meaningfully. After Oct. 7, he turned his dreaming toward the most meaningful dream there is for him: pursuing peace. He believes and works toward a shared Israeli and Palestinian future based on reconciliation, security, safety, and peace. He reminded us that this moment is an opportunity. The sides of this divide will keep arguing and pointing fingers. Palestinians and Israeli Jews can point fingers about who did what to whom forever. But, he believes, it is time to build a future together. Since Oct 7, Inon has begun to “walk the path of peace”. He has begun to appreciate the need to know the “other”’s pain, sorrow, dreams, narratives, and aspirations. We must invest in one another for peace. We must know one another. Along this path he walks, Inon has met many others also walking the path of peace, including Palestinians. He shared with us a teaching he learned from a Palestinian on this path named Hamzeh Hawawde. Hawawde told him: You can forgive the past, you can forgive the present, but you cannot forgive the future. His response?: Amazingly, Inon forgives Hamas for his parents’ Oct. 7 murder. He forgives Netanyahu and the government for his parents’ Oct. 7 murder. He finds meaning in sacrificing life for the purpose of peace. The battle now is how to make peace, and to build a future. We must dream it, talk about it, find partners, and amplify this voice. Astoundingly, he believes that he and the growing camp of voices who are partnering in this work have a strategic plan for a negotiated peace in the next six years. A staff member on our trip, Nadav Tamir, was the one who first mentioned to us that this is a time of crisis, but also an opportunity. And, Inon reminded us that every safe border Israel has was achieved through diplomacy. Negotiations, says Inon, must happen, because it is the only real way forward. This is a chance. Peace with Egypt, peace with Jordan, peace with Qatar—none were achieved through force, but only through diplomatic relations. Only when leaders turned conflict into words of commitment did conflict ever sustainably dissipate. It is hard to capture the charisma and power of Inon’s remarks, but you can perhaps get a better sense of what he has to share by watching his TED Talk here: Aziz Abu Sarah and Maoz Inon: A Palestinian and an Israeli, face to face | TED Talk. When he left us, he made his way to meet the German ambassador. Next month, he will be meeting with the Pope. He is sharing this path the world over. It was a powerful honor to learn from one of the world’s visionaries. I am reminded of the connection between visions and prophecy. There is hope. Keeping Hope Alive: Hostage Square and the Hostage Families Forum Later in the afternoon we visited Hostage Square and the Hostage Families Forum. The square is an open patioed space just outside the Tel Aviv Art Museum. It is filled with posters, signs, and powerful art installations set in vigil for the hostages. I was speechless as I walked through and exhibit that was a replica of a Hamas tunnel through which the viewer was invited to walk. It was installed with posters of hostages and the sound of bombs piped in. It was terrifying and heartbreaking. It was at Hostage Square that I tried to begin memorizing their names. We walked from the square over to a building that houses the Kibbutz movement’s organizational offices. It was in this building that a civil organization blossomed within two days of Oct. 7. These spaces are now home to families of hostages—those released, those deceased, and those who await freedom from captivity. We heard from Gilad Shoham, the father of Tal Shoham, a father in his thirties who is the centerpiece of his family’s life. Both of Gilad’s grandchildren were taken hostage and have since been released. But, without their father, their healing cannot fully cohere. They arrived home in extreme mental unwellness. For Purim, his nine year-old grandson, Naveh, wanted to dress up as a terrorist. His four year-old granddaughter saw rapes, murders, and burnings. They need their dad home. Shoham told us that the Red Cross has been useless to them. The hostage families have met with the Red Cross many times, urging and lobbying for their participation and intervention. They claim that Hamas will not allow it. Yet, the Red Cross is quick to see to the needs of Palestinian prisoners. Unfettered in his remarks he asserted that the Red Cross reticence comes down to not wanting to help Jews. We also heard from Tamar, whose family members were in their Kibbutz shelter when the terrorists came. The shelters were built for bombings, so they had no locks on the doors. Doors were “locked” by an individual on the inside holding it closed with their hand. Itay, a large and imposing man, the father of Lior and Gali held the door closed with all his considerable might. Gali is just thirteen, but she knew, as the smoke began to overtake her brother Lior’s consciousness that they had to get out of there. When the Arabic outside died away, and all seemed quiet, she climbed out of the burning building. Gali was shocked into stillness as she watched a terrorist shoot her dog, Mocha. A terrorist grabbed her, put her on a motorcycle and took her to Gaza. She was there with two other hostages, in an apartment, for 54 days. She had no knowledge of her family. When she was finally released, her family had to tell her that Lior had died that day in the shelter. Itay, who had been shot, was too weak to carry his son’s passed-out body out of the shelter window. When the Red Cross escorted the first released hostages across the border into Israel, Gali was the first one off the van, smiling from ear to ear. As the months have passed, reality has settled in, and the horror and shock of all she has endured has begun to take its toll. When we read the paper or listen to the news we see the posturing and “cards to play” in the geopolitics of the region. Can we leverage the fighting to get the hostages? But, Shoham reminded us of a deep knowing here in Israel: People are not bargaining chips. War or no war, the government has a duty to rescue their citizens. And they are failing to meet this duty. I finally arrived at my hotel twenty hours after departing Allentown. So grateful, but so tired. The trip organizers were able to upgrade our hotel…I can only think it's because hotels have fewer guests right now…I was not expecting to see and experience beauty and pleasure on this trip, but travel sometimes yields its unasked-for jewels. When I entered my room for the evening (really, “night” at this point), I noticed a loud and strange noise coming from the open window. Upon investigating, I saw that it was not a window, but a balcony. The sound was the monumental surf of the seashore, across the street. I gazed upon paradise. It could be so easy to forget that just a few miles away children are suffering underground.

Like many Israeli hotel breakfasts, this morning’s was an array of flavors well beyond the American conception of breakfast…from sweet to savory to umami. Sour to rich. And dark-tasting coffee. Olives and dates and nut-filled pastries. Eggs and cheese and wonderful bread. And salads! It could be so easy to forget that a few miles away there are families who suffer on the brink of famine. It’s hard to figure out how to feel. As I write this overlooking the water, I see runners going by and people splashing their feet in the surf. I am reminded of the interview on NPR with Penina Pfeuffer I quote the other day (previous post). Meghna Chakravarty, the interviewing journalist, asked her to talk about a previous time she had mentioned she could see Gaza from her apartment. She clarified that it was not that she could see Gaza. . . it was that she knew it was only a few miles away. It was not across the globe. It was not what Vietnam was to the United States. It was not as far away from her as Iraq or Afghanistan are/were from us. And, yet, I look out on a peaceful boardwalk. I watch people listening to headphones, their bare feet in the sand. I know that on many US campuses, as I write this, protestors are crying out against “colonialism.” I think for many Jews of older generations this sounds like a woke buzzword. But, this is not a new idea, and it is not a radical one. I remember studying colonialism in college, and I found it to be a profound model for social critique. It has even helped me unpack and enlighten my relationship with Israel (as an American Jew) more ethically through the years. However, as I look at the evidence of leisure and economic prosperity all around me, I do not see colonialism. Colonialism was never about one group prospering while another does not. It is about claiming racial overlordship in a foreign place—a place to which you have no claim. Palestinians may have claim to this land, but it is not without common claim by Jews. What looks like colonialism is just the success of one group with claim to this land. Pollyannish as it may sound, it is my hope that this success, beauty, and blessings may be shared. The vision does not have to be one of enmity. There is a version of Zionism in which this is a Jewish homeland, but that it is not ONLY a Jewish homeland. Being here reminds me of being in the United States . . . we sit miles from center cities bereft of opportunity and safe neighborhoods. And, yet, we turn our eyes away when “the good life” and its moments of pleasure show up on our doorstep. We deserve our prosperity (even if we do not have it) as much as Israeli Jews deserve theirs. Palestinians deserve prosperity just as much, too. Israel cannot make this prosperity happen for non-citizens (to be distinguished from Palestinian citizens of Israel), but it can also do more to stop standing in its way. ----------------------------------------------------- This morning, I slept late in an attempt to recover from my hours and hours of travel. I could hear the surf again, but still did not want to rouse yet. (Our program starts at 1:30pm today). But, then, I heard a siren. I panicked a bit. Surely, no bomb will hit the hotel! I did not know where the shelter was! I looked in the hallway and called out. No answer. I went out on the balcony to see if I could figure out what was going on outside the hotel. People in the street, people on the beach, people in cars, and people on balconies had all stopped and were standing still as the siren wailed. Of course. I had seen film footage of this. I knew about it, but I had never been here to participate in it: on Yom HaShoah (Holocaust Remembrance Day) in Israel at 10:00am, a siren blares. All the Jews in the nation stop where they are and what they are doing and stand at attention--amod dom. I stood on my balcony, participating in this Israeli mitzvah for which I had never had the solemn opportunity. It was powerful and holy. Today is Yom HaShoah. And, yes, people are on the beach and out running. There are surfers and sea kayakers. People are at work. People have their dogs and are doing yoga. But the hotel’s lobby has a banner with a lone flame, along with the word, “Yizkor”—“Remember.” The airport last night was bedecked with the faces of hostages and art exhibits in their honor. The construction site across from the hotel has a huge banner that reads: “Yachad Nanetzach”—“Together We Will Be Victorious.” As anti-Semitism has been rising all around us in the United States, I have begun to see myself in all the old photos from Europe in WWII. The women in these photographs—at home, in transit, under siege, in camps—they seemed to be from another world; a time wholly other and apart. But, more and more each day, as hate rises forthrightly around us, I am seeing myself in them. I see that I am no different. I see that their moment was just like this moment. The black and white of the photography is no longer the protective forcefield it once seemed. And I think how often I forget—how often we in the United States Jewish community forget—how much this nation was built on the shoulders of a national trauma. Not just that Israel’s independence was a result of the Holocaust (scholars debate this), but that the ethos and culture of this place is still a story about trauma. Trauma of 1939, and traumas of 1948 and 1973 and 2001 and 2015. . . But, we are American Jews. We started to build what our Jewish world meant long before this was a state. Our Judaism is about turning aside from so much of our difference (even more so than most of us realize). Life here in Israel is built around being a Jew(ish society) in the wide world with no filter. There is no protective covering of common nationhood beyond one's Jewish identity. Like living on the border with Gaza, I imagine this edge feels like living on the line between life and death. On the living side, it is hard to walk away from a beautiful day at the beach. Postscript: The receptionist at the hotel front desk was kind enough to show me how to get to the shelter in the hotel, which, by the way, she told me, they have not had to use much. |

Rabbi Shoshanah TornbergGrateful to Keneseth Israel of Allentown for the opportunity to travel to Israel at this harrowing time, I go with an open mind, a sorrowful heart, and the need to keep my certainties in check. I hope to learn through listening, and I will share some of that learning here. ArchivesCategories |